I am standing on the beach. The sun is steadily steering toward its zenith. A slight breeze pushes a tiny flock of fair-weather clouds. I barely feel it through the almost see-through weave of my linen shirt brushing the hairs on my arm. Only thanks to those little clouds can I tell the ocean and the sky apart; both blur into shifting shades of blue. At my feet, small waves keep combing the shoreline into Zen-garden patterns. The droplets that remain sparkle in the sun like crystals thrown about with carefree abundance. It’s already so warm that the damp sand feels body-temperature. Today is going to be a good day.

Even surrounded by this display of nature’s beauty, I still carry the duties civilization places on me. To navigate my moment in eternity—even here on the beach—I’m wearing a dive watch. And right now, it bothers me.

The dial is bright blue and has a wave pattern, and all those polished parts are competing to out-sparkle everything else. Technically well executed, sure — but in this setting it strikes me as silly. The reason dawns on me later at the beach bar: a product that imitates nature turns kitsch very fast.

Hmm, I think, dragging my feet through the warm sand, a truly beautiful watch can’t be a copy of nature; it has to make the essence of beauty visible. The sentence “Beauty lies in the eye of the beholder,” from the early aesthete and historian Thucydides, comes to mind. A truth that’s held up for roughly 2400 years. And for one second now I’ve had a wish: I want to find a beautiful dive watch.

That could turn into an odyssey. Dive watches, of all things, are a category that’s almost forfeited beauty. They’re spec-driven and celebrate technical maximalism on the wrist — perhaps the last reserve of a 1980s mindset where watches were about deeper, bigger, farther, expressed in the magic of large numbers. That leads to unwearable dimensions, because the watch could survive a dive to 11,000 meters — strapped to the outside of a submersible, dangling like deep-sea tinsel.

No, superlatives are the wrong direction if you’re chasing beauty.

The other thing I notice, as I trawl the online offerings with a fine-meshed net, is how many ex-Navy, ex-combat-diver, ex-expedition and ex-whatever watches there are. Polished-up veterans of some bygone heroics, their dials plastered with technical promises. Of course all of that at today’s luxury prices.

Both feel kitschy to me: unwearable brag pieces and randomized heroism. So I toss the bycatches of my search back into the digital sea of watch listings.

While I’m sitting in the beach bar, eyes glued to my phone, I miss the weather turning. Well, this is the beach at Kampen on Sylt, not the Caribbean; that’s normal. There’s no such thing as steady weather here. On the same day, everything is possible. From a velvet hour of sunshine to attacks of rain and wind from every direction, maybe except from below. Most of the time you don’t get radiant blue here, but a vast palette of gray. Gray is the real color of this sea, I think. And that gives me an idea. Gray isn’t kitsch; gray is ambiguous.

The beach bar has stopped being a good place.

As the first drops fall, turning patches of my linen shirt transparent, I set off. You don’t find beauty on the internet but with your own eyes. A few hundred meters from the beach in Kampen there’s a very well-stocked authorized dealer. On my way to the beach I already noticed a gray dive watch in the window.

It’s the Blancpain Bathyscaphe in titanium. “Beauty lies in the eye of the beholder.” So what do I see and recognize when the watch lies in front of me?

Strictly speaking, the Bathyscaphe gathers many shades of gray in a dynamic way depending on the light. To me it mirrors the grays of the sky and the sea and everything inside them.

Its titanium dial has a vertical hand-applied brushing that, depending on the light, makes it appear either detailed, silvery-bright or flat, matte gray. The same way the ever-changing sea varies between drowsy, mild moods before sunset and a stormy mood because of an upcoming thunderstorm, when the beach’s ice cream sellers pack up.

On this lively dial, the soft white of the lume plots drifts like foam caps toward the edge. The crystal is domed like the firmament, so visually the dial falls away toward the matte anthracite ceramic bezel — like the sea toward the dark horizon.

The nature associations blend with the tangible: the hands, with their large surfaces, are clearly legible in any weather like position lights; thanks to their ultra-slim tips they’re also as precise to read as a sextant. Their black-polished frames look like light reflecting off portholes and metal fittings.

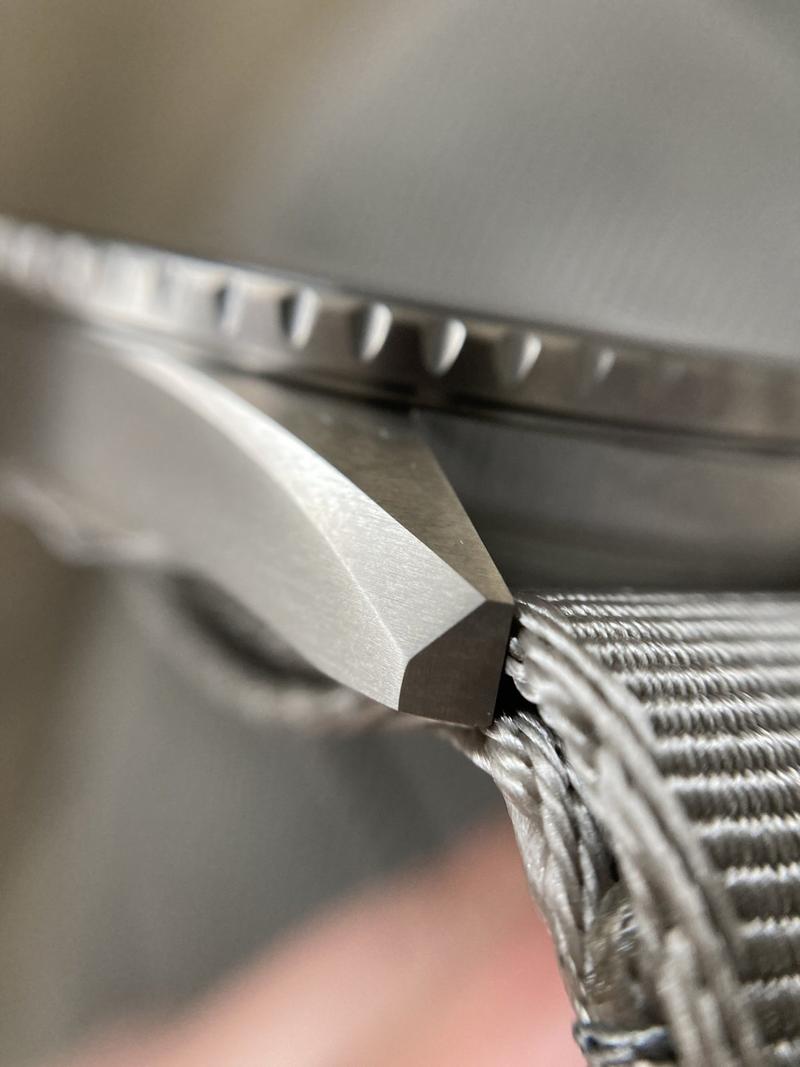

The clearly structured titanium case with its sharp edges is a miniature version of a bow emerging from the waves. Attached to it is the NATO strap — gray and ribbed like fishing nets (and, incidentally, made from them).

The drama of the color play is intensified by the size of the dial. On this gray ocean you’ll only find a very reduced logbook with the bare minimum of text. It’s not clumsy specs, but etymological pointers. Those two lines beneath the brand script have something to say; they whisper their secrets to anyone who can decipher them.

The first clue is the pair of typefaces — not the generic Arial of mass-market watches, but two deliberately different lines of text hinting at what’s to come.

What does “Fifty Fathoms” actually mean?

The first line, Fifty Fathoms, has rich serifs. “Fifty fathoms” are 91.45 meters in an old nautical unit. In the 1950s this was considered the maximum depth a human could dive. And yet a prosaic “100 meters” is not on the dial. Why?

When the Fifty Fathoms launched, Jean-Jacques Fiechter ran Blancpain together with his aunt Betty. By the way, in 1932 Betty Fiechter became the first woman to own and head a Swiss watch manufacturer. It’s well known that, as a passionate diver, he conceived the watch.

What’s hardly known: he held a PhD in history and wrote several novels that even won literary prizes.

Source

Wikipedia

Source

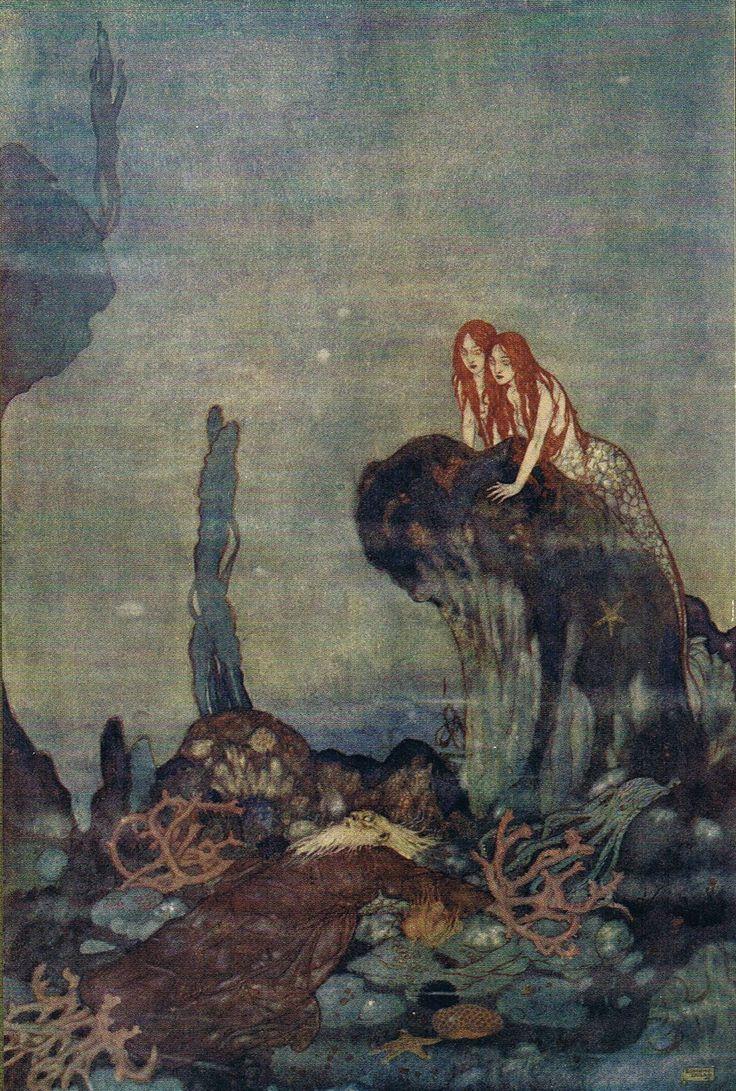

Edmund DulacA mind like that doesn’t write “100 meters” on a dial. The aesthete Dr. Fiechter named his creation after a line from Shakespeare’s play The Tempest. In it, the airy spirit Ariel sings of the King of Naples, drowned in a shipwreck.

“Full fathom five thy father lies; Of his bones are coral made; Those are pearls that were his eyes: Nothing of him that doth fade.”

I like that: specs as a Shakespeare reference.

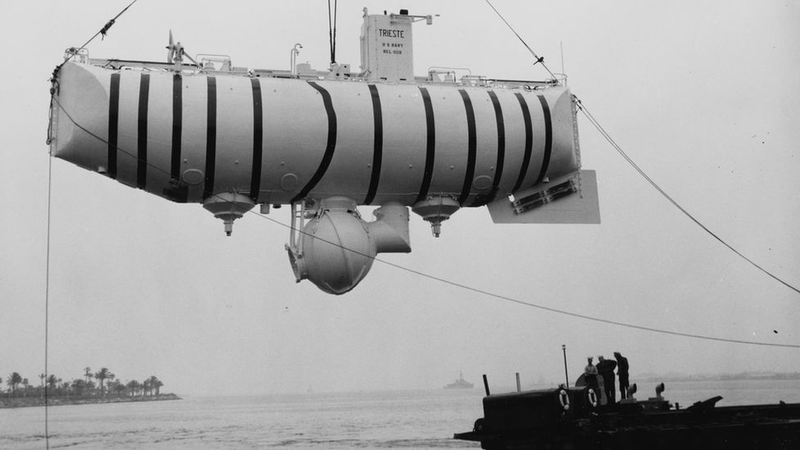

Let’s follow the etymological trail. The second line, set in a technical-looking font, reads Bathyscaphe. This is a reference to the deep-sea submersible of Swiss researcher Auguste Piccard.

Piccard must have been an aesthete, too: although he reached for great deeds, his submersible wasn’t called “Challenger” or anything chest-thumping. He drew on Ancient Greek roots: bathys (“deep”) and skaphos (“ship”). Bathyscaphes are submersibles that are lowered from a mothership for scientific purposes to extreme depths. Again — no superlatives for their own sake; there’s a real goal here: research.

Back from the abstract to the tangible. I pick up the watch. The strikingly angular case shape recalls the inverted silhouette of the namesake submersible. The case is made of titanium in the medical-grade alloy Grade 23, which is very rare in watchmaking. What I especially like is the elaborate satinage: not only does it give the case its submarine kinship, it lends a particularly tactile quality when you run your fingertips across the micro-matte surface.

The proportions are pleasing. When the Bathyscaphe returned in 2013, the worst excesses of the oversized-watch trend were already past. Yes, the spec sheet says 43 mm, but that refers to the bezel, which slightly overhangs for better grip. The case itself is smaller — and, more importantly, wears smaller. The height, at a nearly dainty 13.45 mm among its peers, helps too. Visually the watch appears more compact because the 23 mm strap width and oversized crown skew the proportions to its advantage.

The Bathyscaphe wears very well and exudes calm in every situation. That’s also due to the NATO strap: despite the titanium, the watch feels surprisingly hefty, yet the double-layer construction couples it to the arm with a pleasantly textile softness.

Everything about the watch is executed to an extremely solid standard. The bezel rotates with a loud, satisfying click — like the winch lowering the bathysphere into the sea. You feel the quality when you pull out the oversized crown and stem, and click through the crown’s detents like the engine telegraph on an ocean liner. It almost feels as if container ships could be tied to the crown and be pulled through the Kiel Canal.

Powering it is the same calibre 1315 that debuted in 2007 in the larger Fifty Fathoms as an extra-robust movement for tool watches. It uses enlarged jewels for shock resistance, and the rotor runs in a ceramic bearing. The three barrels not only deliver 120 hours of power reserve, their series arrangement ensures very even torque delivery. Naturally, the movement is regulated in six positions, not just five positions like a chronometer. The result is outstanding accuracy; according to long-time owners it will happily run for ten years without service while keeping fantastic accuracy figures.

So I’m well equipped for rougher circumstances, too. When “hell is empty and all the devils are here”, to paraphrase The Tempest once more. And because the Bathyscaphe uses a full suite of silicon components, the classic soft-iron cage becomes unnecessary and I can admire the movement through a display back.

It’s the same with the movement as with the watch overall: at first glance, it looks rather technical; at second glance, the details and beauty reveals itself. The rotor is the first thing to catch your eye. Under its gray disguise it’s 18k gold and shows three different surface finishes by itself.

Across the movement the patterns are finer, and everything is tone-on-tone. Instead of Geneva stripes, the bridges carry a restrained sunburst that produces wave-like light effects. The engravings are arched and extra small. All bridges have a high-gloss anglage. The screws pop with black polish; select wheels shimmer with a pronounced sunray finish.

I realize I genuinely like this watch. Only one thing makes me pause. As impressive as the dial’s open space is, the proportions between the slim bezel and the small lume plots feel unusual. It’s not the classic face of a diver. As the hero of my own story, I still have a little conflict to resolve.

If this were a purely prosaic watch, I’d simply accept that Blancpain clearly planned the Bathyscaphe as a model family with complications. The three-hander has so much dial real estate because the line also includes a full calendar and a chronograph — each with a lot of information to fill that space.

But I’m not limited to plain prose — beauty lies in my eye. Building on the cultural references seeded by Dr. Fiechter, another one comes to mind that the historian, writer and aesthete would likely have enjoyed.

The interplay of the gray tones of dial and bezel — which I’ve already read as sea and sky — and the small lume plots as sea foam reminds me of the myth of Aphrodite’s birth. Aphrodite — called Venus by the Romans — is the goddess of beauty. She is the daughter of sky and sea, conceived when the sky (under circumstances left discreetly unspoken here) mixed with the saltwater into foam. Aphrodite was born when that foam washed up on the beach. Hence Aphrodite, or Venus Anadyomene — the foam-born.

And so the gray details form a story for me. I now see the Bathyscaphe with different eyes, lean back, and let the case slowly glide through my hand.

My odyssey has ended.

I leave the jeweler with the watch. The sea has calmed down as well; it’s done its blustery day’s work and chased off the tourists who came for blue rather than gray. The masses are gone. Only a few people remain, the ones who enjoy nature. I enjoy it with them.

Write a comment